If We Sing To The Children

I wear these memories

as a cloak to ward off the chill.

Emotions forgotten, but like new now

ripping along my arms,

settling bumps in straight rows

to my heart.

Kindred hearts, matching

my own heartbeat,

with eyes like mine and

reflecting our souls.

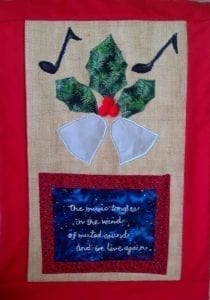

Music in voices saying,

‘and when I look at weeds beside the road. . . .

but you know, you know. . . .’

And I do, I do and we look with eyes

that see and ears that hear the song

of the bird before his sounds

have escaped his throat. . . .

and the music rumbles in our blood,

coursing through our hearts

and gives life only

to those who are ready to listen.

Not many to be sure, not many,

but if we sing to the children

perhaps, just perhaps,

the earth’s cacophony will one day

be harmony.

It is our heritage;

from where it is we come.

From the farm country I was given

a substance that does not spoil,

that does not turn sour

even in the residue of life.

It is not dregs that I drink.

It is the cream rising to the top of the milk.

I needed to see a skyline

with no obstruction and with no words

you laid your hearts on me.

8/11/14 photo by John Holmes