The Teacher Speaks. . . . Any human action which must delve into its past for a pattern for progression is bound to fail. There must of needs be new attitudes, new forms of behavior that speaks to the new man and new times. A reaching back to the cradle for behavior, for mannerisms befitting the child to become adult is never a course of action to follow. The state of the progression must be one to choose an upward and though tentative step, it must be forward to be progression at all. The past must be forgiven its transgressions because those involved were not adult enough to know better. They truly did not know what they do. And because in our new knowledge, we do, we forgive but do not forget ever the behaviors that crippled us. And we will live never to inflict hurt upon those we touch. Let our attitudes be such that there will be gratitude in that we lived.

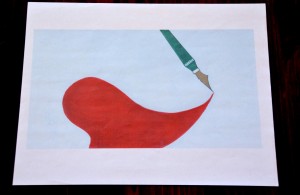

Suffer The Little Child

There are magic words

in my head

and yours, too,

turning upon themselves

like prayers. They invoke

graven images

cast upon the mind

in forms to be worshiped.

We uncover them like idols

in the churches of our choice,

when the season or

the time of solstice

assures us this is proper.

We bow before them

with reverence.

We pay homage or penance

for untold sins

and beg forgiveness for our humanness.

We forget we once

shared space with them,

helping to make them so beautiful.

Instead, we consign ourselves

to these words of magic

and pretend that we are

what we always were.

Denying ourselves a profit,

commensurate with our work,

we suffer the little child, forever.